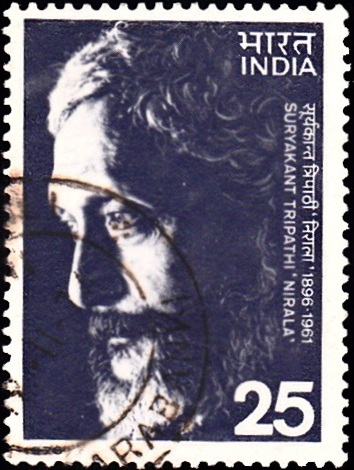

Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’

A commemorative postage stamp on the Death Anniversary of Suryakant Tripathi Nirala, an Indian Hindi Chhayavaad poet, novelist, essayist and story-writer :

Issued by India

Issued on Oct 15, 1976

Issued for : The Indian Posts & Telegraphs Department is happy to bring out a postage stamp in honour of this great son of India.

Type : Stamp, Postal Used

Colour : Blue grey

Denomination : 25 Paise

Overall size : 3.91 X 2.90 cms.

Printing size : 3.56 X 2.54 cms.

Perforation : 13 x 13

Watermark : Unwatermarked paper

Number printed : 30,00,000

Number per issue sheet : 35

Printing process : Photogravure

Designed and printed at : India Security Press

Name : Dinbandhu Nirala

Born on Feb 21, 1896 at Midnapore, West Bengal, India

Died on Oct 15, 1961 at Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, India

About :

- Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’, one of the greatest Hindi poets of all times, was born on February 16, 1896. His father, Ram Sahai Tripathi, held double charge under the then King of Mahishadal in Bengal as a Police Officer and keeper of the State Treasury. His mother died when he was hardly 3 years old.

- ‘Nirala‘ had his formal education only up to the 10th standard. However, he had already developed a great interest in Bengali, English, Sanskrit and Hindi literatures, thanks to the rich Royal Library at Mahishadal. He also excelled in singing, wrestling, shooting and writing. It was during his adolescence that he was introduced to the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore who inspired him to be a poet.

- ‘Nirala‘ was married at the age of 15. His wife, Manohara Devi, was a great lover of Hindi and it was partly due to her inspiration that ‘Nirala‘ started writing poetry in Hindi. ‘Nirala‘ had a son and a daughter – the latter’s death at the young age of 18 moved him to write one of the greatest elegies in Hindi poetry – Saroj Smriti. ‘Nirala‘s wife died in 1918.

- ‘Nirala‘ was an independent man with a high sense of self-respect. He could not continue for long in Mahishadal and got interested in the teachings of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa as well as the National Movement for Independence and the struggles of farmers and workers. He resigned from his job in 1920 and decided to live on writing alone.

- ‘Nirala‘ had started writing in 1916 and already had such a finished poem as Juhi Ki Kali behind him. His first collection of verse Anamika was published in 1922. He was offered the editorship of the Matwala in 1923 which he edited with rare zeal and insight. It was then that he started writing under the nom de plume ‘Nirala‘.

- The concept of ‘free verse’ or blank verse was almost unknown in Hindi till then. ‘Nirala‘ broke the bonds of rhyme and metre and in the face of almost universal antagonism championed the case of free verse in Hindi. He was ridiculed, boycotted and condemned for this, but he had such indomitable courage of his conviction that he lived to see free verse firmly established in Hindi. It would, however, be erroneous to suppose that he could not write in rhyme or metre. Many of his best poems follow the rules of traditional poetry as well. ‘Nirala‘ was a restless spirit and he shifted from Calcutta to Varanasi and went back to his ancestral village Garhrakola. From there he went on to edit the Sudha at Lucknow and mature works like Geetika, Tulsidas (poetry), Alka and Apsara (novels) were written here. He left Lucknow in 1940 and staying briefly at Unnao, Allahabad and Varanasi, finally settled down in Allahabad.

- Though ‘Nirala‘ is known primarily as a poet, he has few rivals in the field of prose. In his novels like Billesurebakariha and short stories like Chaturi Chamar and Sukul ki Bibi, he writes about struggling men and women of India in a style that is bereft of ornamentation and is extremely powerful in its stark directness.

- ‘Nirala‘s life was one of tragedies, struggle and chronic poverty. The poet in him refused to bow before any individual. ‘Nirala‘ remained a fighter throughout his life and had to pay a heavy psychological price for it. He died in Allahabad on October 15, 1961. While he was often on the verge of penury, he would give away whatever money he had and even clothes, to the poor around him.